Ruskin Spear (1911-1990)

Provenance

Sotheby’s London 15th July 1998 ;

Christie’s, South Kensington 14th October 2004;

Julian Hartnoll;

Private Collection UK

Exhibitions

Royal Academy, 1969, no 568

Royal Institute of Fine Arts, 1969

Ruskin Spear studied at the Hammersmith School of Art and then at the Royal College of Art (where he subsequently taught between 1948 and 1977). Excused military service in WWII on account of childhood polio, he instead took part in the ‘Recording Britain’ scheme initiated by the government at that time.

The work of Walter Sickert (1860-1942) was a strong influence on Spear throughout his career. Sickert’s fascination with the low-life scenes of Camden Town is reflected in Spear’s own life-long interest in painting scenes of everyday life in his native Hammersmith. Spear’s style soon developed into a highly recognizable one of casual, informal observation. He also developed a successful practice as a portrait painter, but even these pictures he imbued with a sense of the improvised rather than the carefully arranged. His sitters are presented as people glanced at swiftly or even taken unawares. Like Sickert before him, Spear liked the newspaper photographer’s ‘snapshots’ of people; indeed some of his portraits were worked directly from newspaper cuttings. But all of Spear’s portraits tend to show the sitter in unposed, unguarded moments. His sitters were drawn from the whole range of society. He would paint the ordinary man-in-the-street one day and then the next he would be called upon to paint Harold Wilson, John Betjeman or Laurence Olivier. Spear’s oeuvre forms a distinctive body of figurative art in post-war Britain and his work hangs in numerous public collections. In London there are holdings at Tate Britain, The Imperial War Museum and the National Portrait Gallery. Among the provincial galleries, Bristol, Nottingham and Sheffield have good representations. A number of universities also chose Spear to portray their senior academics. He was particularly popular with Oxford and Cambridge Colleges, and Spear’s portraits can be seen hanging in their public spaces today.

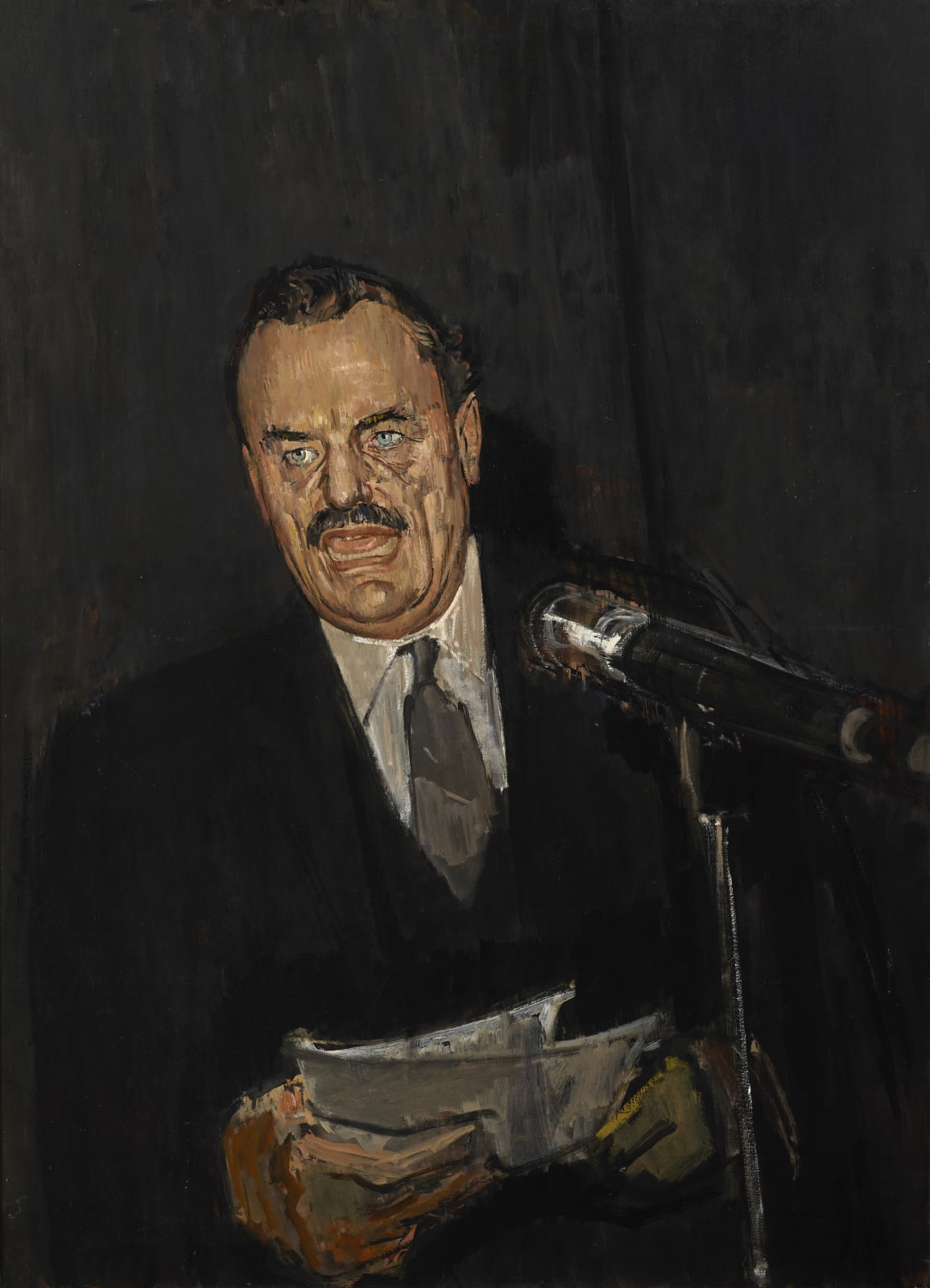

Despite its conventionally neutral titling, Study against a Black Background was instantly recognizable at the time of its initial exhibition as a portrait of the M.P. Enoch Powell (1912-1998). Powell was one of the United Kingdom’s most brilliant and controversial twentieth-century politicians. He was educated at Trinity College Cambridge, where, after taking a double first in Latin and Greek, he remained briefly as a fellow. He was then appointed Professor of Greek at the University of Sydney at the remarkably young age of 25. When WWII broke out he returned home, enlisting as a private in the Royal Warwickshire Regiment although he was soon seconded to Military Intelligence. He saw no action, but initially was closely involved in the strategic planning of the defeat of Rommel in North Africa. In 1943 he transferred to Intelligence in Delhi, working first with Mountbatten and later in 1944 providing intelligence support for General Slim’s Burma campaign. Remarkably, he finished the war as a Brigadier with an OBE, an extraordinary rise from his status as private at its beginning.

Returning to England after the war, Powell set his sights on politics. After one failure in the general election of 1947, he was elected as the member for Wolverhampton South West, a seat he held until 1974. Thereafter, disenchanted with the government of Edward Heath, he resigned from the Conservative Party and was elected instead for the constituency of South Down where he sat as an Ulster Unionist until finally losing his seat in 1987. His three most notable political posts were Financial Secretary to the Treasury (1957-58), Minister of Health (1960-63), and Shadow Secretary of Defence (1965-68).

In this present picture, Ruskin Spear shows us Powell delivering what was probably not his most important speech as a politician, but certainly the one by which most people remember him today: the so-called “Rivers of Blood” speech, delivered in Birmingham on the 20th April 1968 at the West Midlands Area Conservative Political Centre. At the time, there was a bill on race relations going through parliament that proposed to make discrimination on racial grounds illegal.

Powell took this opportunity to rail against large-scale immigration to the country, which he felt would soon overwhelm the population if not controlled. He specifically targeted Black and Asian immigrants from the Commonwealth countries. In this speech - a subject still debated today - Powell stated his view that: “We must be mad, literally mad as a nation” to allow immigration on such a large scale. Quoting Virgil, he continued: “As I look ahead I am filled with foreboding. Like the Roman, I seem to see the River Tiber foaming with much blood”. This incendiary metaphor, picked up almost universally by the press at the time, is how the speech is remembered and referred to today.

Study against a Black Background must number amongst Spear’s most powerful canvases. The artist was not present as the speech was being delivered, but in a manner reminiscent of his idol Sickert, he has pieced his portrait together from newspaper cuttings and other reportage of the day. With his typical asymmetric sense of composition, Spear has Powell almost lurching to one side. But Spear also positions his subject right up in the front plane of the picture, where he has him effectively bursting out of the frame. In this way the artist ensures that the viewer is not only completely connected to the speaker and his speech, but nearly overwhelmed by them. It is known that Spear initially painted the picture in a totally unrelieved dark colour scheme, but that towards the end of the process he added the tonal contrast of the light-coloured microphone. The microphone was not present on that April evening in 1968, but it does form an intelligent and necessary counterpoint to the solid dark colours of Powell’s clothing and acts as a scale-giving repoussoir for the viewer. Spear’s title for the painting, Study against a Black Background, is surely a conscious allusion to the political issues of race and colour as much as it is a typical artistic reference to pictorial composition. But in the end the title remains ambiguous. The artist was questioned about it at the time, but he would not be drawn, saying only that he wanted viewers to make up their own minds. The painting was exhibited at the Royal Academy in 1969 where it made a huge impact and, despite effectively commemorating an event that was already a year old, it garnered all the headlines of the day. It is a portrait that has lost none of its force today. Like the difficult maverick but significant politician whom it portrays, it still has the power to arrest and divide its viewers half a century later.