James Hall Nasmyth (1808-1890)

Provenance

By descent in the Maudslay family

In 1829, Nasmyth (then 20), determined to join the firm of engineers and tool-makers of Henry Maudslay in London: ‘I was told that his works were the very centre and climax of all that was excellent in mechanical workmanship’ (James Nasmyth (ed. Samuel Smiles), James Nasmyth, Engineer - An Autobiography, John Murray, London 1883, p 120).

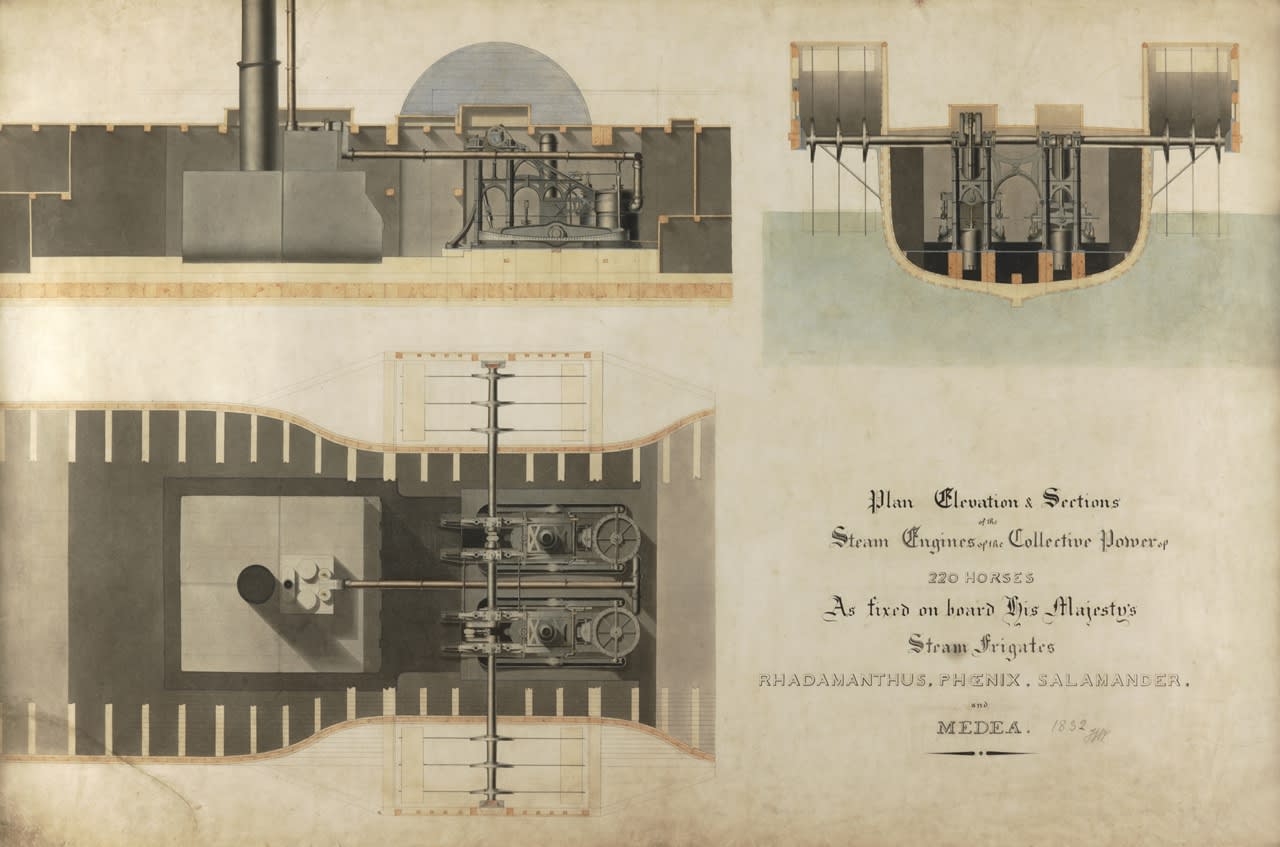

Maudslay disliked taking on of ‘premium’ (paying) apprentices. To persuade him, Nasmyth showed him a working model of one of Maudslay’s own steam engines, that he had built himself, right down to the forging and casting of every component, as well as a set of mechanical drawings he had made. Maudslay was so impressed he took Nasmyth on as his personal assistant workman, and gave him a salary. Maudslay at this time was building a new marine engine of unprecedented power and efficiency (at his own risk because it had not been commissioned). It proved successful, however, and further engines of 220 hp were then commissioned by the Admiralty. Nasmyth was tasked by Maudslay to draw them: ‘Mechanical drawing is the alphabet of the engineer. Without this the workman is merely,a “hand.” With it he indicates the possession of “a head" [...] It was a branch of delineative art that my father had carefully taught me. Throughout my professional life I have found this art to be of the utmost practical value’ (ibid, p 122). Nasmyth, whose father was the Edinburgh portrait and landscape painter Alexander Nasmyth, went on to a distinguished career as one of the great engineers of the Industrial Revolution, including the invention of the steam hammer. He was also an amateur astronomer, and built his own telescopes.

One of the Royal Navy ships this engine was installed in, the Medea, could steam 1,360 miles at 10 knots, and was considered fit for any long-distance passage save a westerly voyage across the Atlantic in winter. She and her sister ships revolutionised sea power.